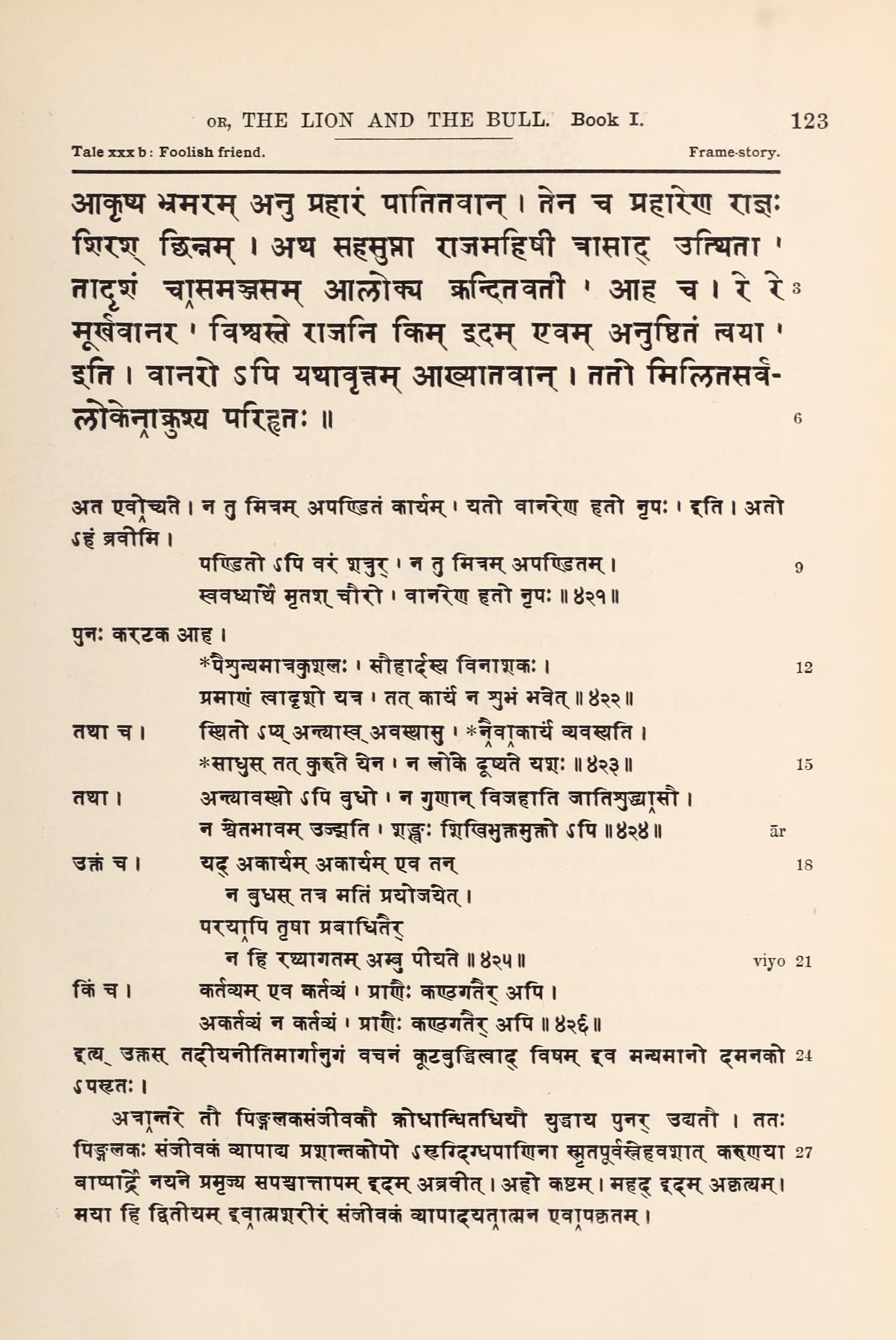

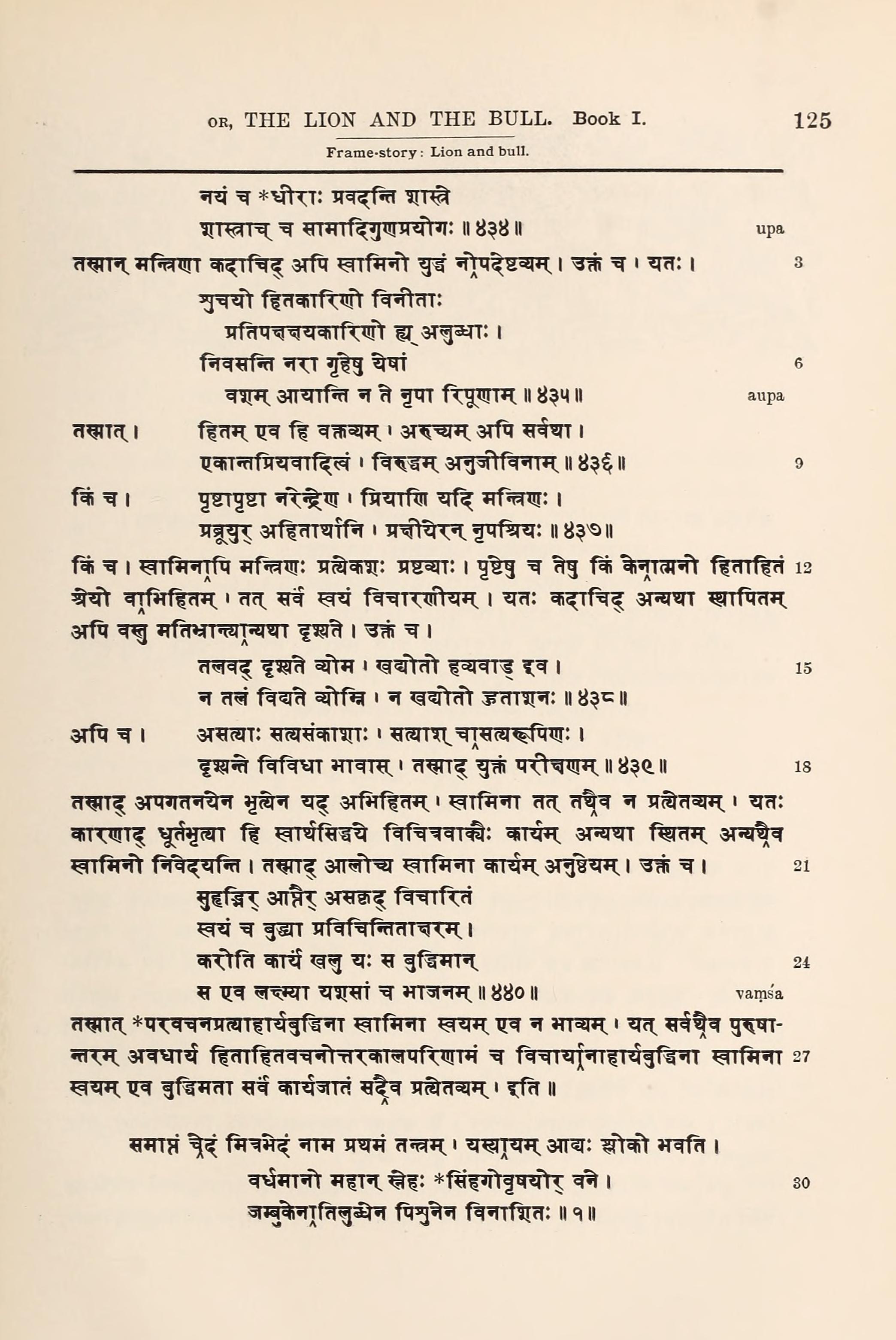

Here then begins Book I, called “The Loss of Friends.” The first verse runs:

The forest lion and the bull Were linked in friendship, growing, full: A jackal then estranged the friends For greedy and malicious ends.

And this is how it happened.

In the southern country was a city called Maidens’ Delight. It rivaled the city of heaven’s King, so abounding in every urban excellence as to form the central jewel of Earth’s diadem. Its contour was like that of Kailasa Peak. Its gates and palaces were stocked with machines, missile weapons, and chariots in great variety. Its central portal, massive as Indrakila Mountain, was fitted with bolt and bar, panel and arch, all formidable, impressive, solid. Its numerous temples lifted their firm bulk near spacious squares and crossings. It wore a moat-girdled zone of walls that recalled the high-uplifted Himalayas.

In this city lived a merchant named Increase. He possessed a heap of numerous virtues, and a heap of money, a result of the accumulation of merit in earlier lives.

As he once pondered in the dead of night, his conclusions took this form: “Even an abundant store of wealth, if pecked at, sinks together like a pile of soot. A very little, if added to, grows like an ant-hill. Hence, even though money be abundant, it should be increased. Riches unearned should be earned. What is earned, should be guarded. What is guarded, should be enlarged and heedfully invested. Money, even if hoarded in commonplace fashion, is likely to go in a flash, the hindrances being many. Money unemployed when opportunities arise, is the same as money unpossessed. Therefore, money once acquired should be guarded, increased, employed. As the proverb says:

Release the money you have earned;

So keep it safely still:

The surplus water of a tank

Must find a way to spill.

Wild elephants are caught by tame;

With capital it is the same:

In business, beggars have no scope

Whose stock-in-trade is empty hope.

If any fail to use his fate

For joy in this or future state,

His riches serve as foolish fetters;

He simply keeps them for his betters.”

Having thus set his mind in order, he collected merchandise bound for the city of Mathura, assembled his servants, and after saying farewell to his parents when asterism and lunar station were auspicious, set forth from the city, with his people following and with blare of conch-shell and beat of drum preceding. At the first water he bade his friends turn back, while he proceeded.

To bear the yoke he had two bulls of good omen. Their names were Joyful and Lively; they looked like white clouds, and their chests were girded with golden bells.

Presently he reached a forest lovely with grisleas, acacias, dhaks, and sals, densely planted with other trees of charming aspect; fearsome with elephants, wild oxen, buffaloes, deer, grunting-cows, boars, tigers, leopards, and bears; abounding in water that issued from the flanks of mountains; rich in caves and thickets.

Here the bull Lively was overcome, partly by the excessive weight of the wagon, partly because one foot sank helpless where far-flung water from cascades made a muddy spot. At this spot the bull somehow snapped the yoke and sank in a heap. When the driver saw that he was down, he jumped excitedly from the wagon, ran to the merchant not far away, and humbly bowing, said: “Oh, my lord! Lively was wearied by the trip, and sank in the mud.”

On hearing this, merchant Increase was deeply dejected. He halted for five nights, but when the poor bull did not return to health, he left caretakers with a supply of fodder, and said: “You must join me later, bringing Lively, if he lives; if he dies, after performing the last sad rites.” Having given these directions, he started for his destination.

On the next day, the men, fearing the many drawbacks of the forest, started also and made a false report to their master. “Poor Lively died,” they said, “and we performed the last sad rites with fire and everything else.” And the merchant, feeling grieved for a mere moment, out of gratitude performed a ceremony that included rites for the departed, then journeyed without hindrance to Mathura.

In the meantime, Lively, since his fate willed it and further life was predestined, hobbled step by step to the bank of the Jumna, his body invigorated by a mist of spray from the cascades. There he browsed on the emerald tips of grass-blades, and in a few days grew plump as Shiva’s bull, high-humped, and full of energy. Every day he tore the tops of anthills with goring horns, and frisked like an elephant.

But one day a lion named Rusty, with a retinue of all kinds of animals, came down to the bank of the Jumna for water. There he heard Lively’s prodigious bellow. The sound troubled his heart exceedingly, but he concealed his inner feelings while beneath a spreading banyan tree he drew up his company in what is called the Circle of Four.

Now the divisions of the Circle of Four are given as: (1) the lion, (2) the lion’s guard, (3) the understrappers, (4) the menials. In all cities, capitals, towns, hamlets, market-centers, settlements, borderposts, land-grants, monasteries, and communities there is just one occupant of the lion’s post. Relatively few are active as the lion’s guard. The understrappers are the indiscriminate throng. The menials are posted on the outskirts. The three classes are each divided into members high, middle, and low.

Now Rusty, with counselors and intimates, enjoyed a kingship of the following order. His royal office, though lacking the pomp of umbrella, flyflap, fan, vehicle, and amorous display, was held erect by sheer pride in the sentiment of unaffected pluck. It showed unbroken haughtiness and abounding self-esteem. It manifested a native zeal for unchecked power that brooked no rival. It was ignorant of cringing speech, which it delegated to those who like that sort of thing. It functioned by means of impatience, wrath, haste, and hauteur. Its manly goal was fearlessness, disdaining fawning, strange to obsequiousness, unalarmed. It made use of no wheedling artifices, but glittered in its reliance on enterprise, valor, dignity. It was independent, unattached, free from selfish worry. It advertised the reward of manliness by its pleasure in benefiting others. It was unconquered, free from constraint and meanness, while it had no thought of elaborating defensive works. It kept no account of revenue and expenditure. It knew no deviousness nor time-serving, but was prickly with the energy earned by loftiness of spirit. It wasted no deliberation on the conventional six expedients, nor did it hoard weapons or jewelry. It had an uncommon appetite for power, never adopted subterfuges, was never an object of suspicion. It paid no heed to wives or ambush-layers, to their torrents of tears or their squeals. It was without reproach. It had no artificial training in the use of weapons, but it did not disappoint expectations. It found satisfactory food and shelter without dependence on servants. It had no timidity about any foreign forest, and no

alarms. Its head was high. As the proverb says:

The lion needs, in forest station,

No trappings and no education,

But lonely power and pride;

And all the song his subjects sing,

Is in the words: “O King! O King!”

No epithet beside.

And again:

The lion needs, for his appointing, No ceremony, no anointing; His deeds of heroism bring Him fortune. Nature crowns him king. The elephant is the lion's meat, With drops of trickling ichor sweet; Though lack thereof should come to pass, The lion does not nibble grass.

Now Rusty had in his train two jackals, sons of counselors, but out of a job. Their names were Cheek and Victor. These two conferred secretly, and Victor said: “My dear Cheek, just look at our master Rusty. He came this way for water. For what reason does he crouch here so disconsolate?” “Why meddle, my dear fellow?” said Cheek. “There is a saying:

Death pursues the meddling flunkey: Note the wedge-extracting monkey.”

“How was that?” asked Victor. And Cheek told the story of

The Wedge-Pulling Monkey

There was a city in a certain region. In a grove near by, a merchant was having a temple built. Each day at the noon hour the foreman and workers would go to the city for lunch.

Now one day a troop of monkeys came upon the half-built temple. There lay a tremendous anjana-log, which a mechanic had begun to split, a wedge of acacia-wood being thrust in at the top.

There the monkeys began their playful frolics upon tree-top, lofty roof, and woodpile. Then one of them, whose doom was near, thoughtlessly bestrode the log, thinking: “Who stuck a wedge in this queer place?” So he seized it with both hands and started to work it loose. Now what happened when the wedge gave at the spot where his private parts entered the cleft, that, sir, you know without being told.

“And that is why I say that meddling should be avoided by the intelligent. And you know,” he continued, “that we two pick up a fair living just from his leavings.”

“But,” said Victor, “how can you give first-rate service merely from a desire for food with no desire for distinction? There is wisdom in the saying:

In hurting foes and helping friends The wise perceive the proper ends Of serving kings. The belly's call To answer, is no job at all.

And again:

When many lives on one depend,

Then life is life indeed:

A crow, with beak equipped, can fill

His belly's selfish need.

If loving kindness be not shown

To friends and souls in pain,

To teachers, servants, and one's self,

What use in life, what gain?

A crow will live for many years

And eat the offered grain.

A dog is quite contented if

He gets a meatless bone,

A dirty thing with gristle-strings

And marrow-fat alone—

And not enough of it at that

To still his belly's moan.

The lion scorns the jackal, though

Between his paws, to smite

The elephant. For everyone,

However sad his plight,

Demands the recompense that he

Esteems his native right.

Dogs wag their tails and fawn and roll,

Bare mouth and belly, at your feet:

Bull-elephants show self-esteem,

Demand much coaxing ere they eat.

A tiny rill

Is quick to fill,

And quick a mouse's paws;

So seedy men

Are grateful, when

There is but little cause.

For if there be no mind

Debating good and ill,

And if religion send

No challenge to the will,

If only greed be there

For some material feast,

How draw a line between

The man-beast and the beast?

Or more accurately yet:

Since cattle draw the plow

Through rough and level soil,

And bend their patient necks

To heavy wagons' toil,

Are kind, of sinless birth,

And find in grass a feast,

How can they be compared

With any human beast?”

“But at present,” said Cheek, “we two hold no job at court. So why meddle?” “My dear fellow,” said Victor, “after a little the jobless man does hold a job. As the saying goes:

The jobless man is hired

For careful serving;

The holder may be fired,

If undeserving.

No character moves up or down

At others' smile or others' frown;

But honor or contempt on earth

Will follow conduct's inner worth.

And once more:

It costs an effort still To carry stones uphill; They tumble in a trice: So virtue, and so vice.”

“Well,” said Cheek, “what do you wish to imply?” And Victor answered: “You see, our master is frightened, his servants are frightened, and he does not know what to do.” “How can you be sure of that?” asked Cheek, and Victor said: “Isn’t it plain?

An ox can understand, of course, The spoken word; a driven horse Or elephant, exerts his force; But men of wisdom can infer Unuttered thought from features' stir— For wit rewards its worshiper.

And again:

From feature, gesture, gait,

From twitch, or word,

From change in eye or face

Is thought inferred.

So by virtue of native intelligence I intend to get him into my power this very day.”

“Why,” said Cheek, “you do not know how to make yourself useful to a superior. So tell me. How can you establish power over him?”

“And why, my good fellow, do I not know how to make myself useful?” said Victor. “The saintly poet Vyasa has sung the entry of the Pandu princes into Virata’s court. From his poem I learned the whole duty of a functionary. You have heard the proverb:

No burden enervates the strong; To enterprise no road is long; The well-informed all countries range; To flatterers no man is strange.”

But Cheek objected: “He might perhaps despise you for forcing yourself into a position that does not belong to you.” “Yes,” said Victor, “there is point in that. However, I am also a judge of occasions. And there are rules, as follows:

The Lord of Learning, speaking to

A false occasion,

Will meet with hatred, and of course

Lack all persuasion.

And again:

The favorite's business comes to be A sudden source of king's ennui, When he is thoughtful, trying scents, Retiring, or in conference.

And once again:

On hours of talk or squabbling rude,

Of physic, barber, flirting, food,

A gentleman does not intrude.

Let everyone be cautious

In palaces of kings;

And let not students rummage

In their professor's things:

For naughty meddlers suffer

Destruction swift and sure,

Like evening candles, lighted

In houses of the poor.

Or put it this way:

On entering a palace,

Adjust a modest dress;

Go slowly, bowing lowly

In timely humbleness;

And sound the kingly temper,

And kingly whims no less.

Or this way:

Though ignorant and common,

Unworth the honoring,

Men win to royal favor

By standing near the king:

For kings and vines and maidens

To nearest neighbors cling.

And once again:

The servant in his master's face Discerns the signs of wrath and grace, And though the master jerk and tack, The servant slowly mounts his back.

And finally:

The brave, the learnèd, he who wins

To bureaucratic power

These three, alone of all mankind,

Can pluck earth's golden flower.

“Now let me inform you how power is gained by dancing attendance on a master.

Win the friendly counselors,

To the monarch dear,

Win persuasive speakers; so

Gain the royal ear.

On the undiscerning mob

'Tis not wise to toil:

No man reaps a harvest by

Plowing barren soil.

Serve a king of merit, though

Friendless, destitute;

After some delay, you pluck

Long-enduring fruit.

Hate your master, and you fill

Servant's meanest state:

Not discerning whom to serve,

'Tis yourself you hate.

Treat the dowager, the queen,

And the king-to-be,

Chaplain, porter, counselor,

Most obsequiously.

One who seeks the van in fights,

In the palace clings,

In the city walks behind,

Is beloved of kings.

One who flatters when addressed,

Does the proper things.

Acts without expressing doubts.

Is beloved of kings.

One, the royal gifts of cash

Prudently who flings,

Wearing gifts of garments, he

Is beloved of kings.

One who never makes reply

That his master stings,

Never boisterously laughs,

Is beloved of kings.

One who never hearkens to

Queenly whisperings,

In the women's quarters dumb,

Is beloved of kings.

One who, even in distress,

Never boasts and sings

Of his master's favor, he

Is beloved of kings.

One who hates his master's foe,

Loves his friend, and brings

Pain or joy to either one,

Is beloved of kings.

One who never disagrees,

Blames, or pulls the strings

Of intrigue with enemies,

Is beloved of kings.

One who finds in battle, peace

Free from questionings,

Thinks of exile as of home,

Is beloved of kings.

One who thinks of dice as death,

Wine as poison-stings,

Others' wives as statues, he

Is beloved of kings.”

“Well,” said Cheek, “when you come into his presence, what do you intend to say first? Please tell me that.” And Victor replied:

“Answers, after speech begins,

Further answers breed,

As a seed, with timely rain,

Ripens other seed.

And besides:

A clever servant shows his master The gleam of triumph or disaster From good or evil courses springing, And shows him wit, decision-bringing. The man possessing such a wit Should magnify and foster it; Thereby he earns a livelihood And public honor from the good.

And there is a saying:

Let anyone who does not seek His master's fall, unbidden speak; So act at least the excellent: The other kind are different.”

“But,” said Cheek, “kings are hard to conciliate. There is a saying:

In sensuous coil

And heartless toil,

In sinuous course

And armored force,

In savage harms

That yield to charms—

In all these things

Are snakes like kings.

Uneven, rough,

And high enough—

Yet low folk roam

Their flanks as home,

And wild things haunt

Them, hungry, gaunt—

In all these things

Are hills like kings.

The things that claw, and the things that gore

Are unreliable things;

And so is a man with a sword in his hand,

And rivers, and women, and kings.”

“Quite true,” said Victor. “However:

The clever man soon penetrates The subject's mind, and captivates.

Cringe, and flatter him when angry;

Love his friend and hate his foe;

Duly advertise his presents—

Trust no magic—win him so.

And yet:

If a man excel in action,

Learning, fluent word,

Make yourself his humble servant

While his power is stirred,

Quick to leave him at the moment

When he grows absurd.

Plant your words where profit lies:

Whiter cloth takes faster dyes.

Till you know his power and manhood,

Effort has no scope:

Moonlight's glitter vainly rivals

Himalaya's slope.”

And Cheek replied: “If you have made up your mind, then seek the feet of the king. Blest be your journeyings. May your purpose be accomplished.

Be heedful in the presence of the king; We also to your health and fortune cling.”

Then Victor bowed to his friend, and went to meet Rusty.

Now when Rusty saw Victor approaching, he said to the doorkeeper: “Away with your reed of office! This is an old acquaintance, the counselor’s son Victor. He has free entrance. Let him come in. He belongs to the second circle.” So Victor entered, bowed to Rusty, and sat down on the seat indicated to him.

Then Rusty extended a right paw adorned with claws as formidable as thunderbolts, and said respectfully: “Do you enjoy health? Why has so long a time passed since you were last visible?” And Victor replied: “Even though my royal master has no present need of me, still I ought to report at the proper time. For there is nothing that may not render service to a king. As the saying goes:

To clean a tooth or scratch an ear

A straw may serve a king:

A man, with speech and action, is

A higher kind of thing.

“Besides, we who are ancestral servants of our royal master, follow him even in disasters. For us there is no other course. Now the proverb says:

Set in fit position each

Gem or serving-man;

No tiaras on the toes,

Just because you can.

Servants leave the kings who their

Qualities ignore,

Even kings of lofty line,

Wealthy, served of yore.

Lacking honor from their equals,

Jobless, déclassé,

Servants give their master notice

That they will not stay.

And again:

If set in tin, a gem that would

Adorn a golden frame,

Will never scream nor fail to gleam,

Yet tells its wearer's shame.

The king who reads a servant's mind—

Dull, faithless, faithful, wise—

May servants find of every kind

For every enterprise.

“And as for my master’s remark: ‘It is long since you were last visible,’ pray hear the reason of that:

Where just distinction is not drawn

Between the left and right,

The self-respecting, if they can,

Will quickly take to flight.

If masters no distinction make

Among their servants, then

They lose the zealous offices

Of energetic men.

And in a market where it seems

That no distinctions hold

Between red-eye and ruby, how

Can precious gems be sold?

There must be bonds of union

In all their dealings, since

No prince can lack his servants

Nor servants lack a prince.

“Yet the nature of the servant also depends on the master’s quality. As the saying goes:

In case of horse or book or sword, Of woman, man or lute or word, The use or uselessness depends On qualities the user lends.

“And another point. You do wrong to despise me because I am a jackal. For

Silk comes from worms, and gold from stone; From cow's hair sacred grass is grown; The water-lily springs from mud; From cow-dung sprouts the lotus-bud; The moon its rise from ocean takes; And gems proceed from hoods of snakes; From cows' bile yellow dyestuffs come; And fire in wood is quite at home: The worthy, by display of worth, Attain distinction, not by birth.

And again:

Kill, although domestic born,

Any hurtful mouse:

Bribe an alien cat who will

Help to clean the house.

And once again:

How use the faithful, lacking power?

Or strong, who evil do?

But me, O King, you should not scorn,

For I am strong and true.

Scorn not the wise who penetrate

Truth's universal law;

They are not men to be restrained

By money's petty straw:

When beauty glistens on their cheeks

By trickling ichor lent,

Bull-elephants feel lotus-chains

As no impediment.”

“Oh,” said Rusty, “you must not say such things. You are our counselor’s son, an old retainer.” “O King,” said Victor, “there is something that should be said.” And the king replied: “My good fellow, reveal what is in your heart.”

Then Victor began: “My master set out to take water. Why did he turn back and camp here?” And Rusty, concealing his inner feelings, said: “Victor, it just happened so.” “O King,” said the jackal, “if it is not a thing to disclose, then let it be.

Some things a man should tell his wife,

Some things to friend and some to son;

All these are trusted. He should not

Tell everything to everyone.”

Hereupon Rusty reflected: “He seems trustworthy. I will tell him what I have in mind. For the proverb says:

You find repose, in sore disaster, By telling things to powerful master, To honest servant, faithful friend, Or wife who loves you till the end.

Friend Victor, did you hear a great voice in the distance?” “Yes, master, I did,” said Victor. “What of it?”

And Rusty continued: “My good fellow, I intend to leave this forest.” “Why?” said Victor. “Because,” said Rusty, “there has come into our forest some prodigious creature, from whom we hear this great voice. His nature must correspond to his voice, and his power to his nature.”

“What!” said Victor. “Is our master frightened by a mere voice? You know the proverb:

Water undermines the dikes; Love dissolves when malice strikes; Secrets melt when babblings start; Simple words melt dastard hearts.

So it would be improper if our master abruptly left the forest which was won by his ancestors and has been so long in the family. For they say:

Wisely move one foot; the other

Should its vantage hold;

Till assured of some new dwelling,

Do not leave the old.

“Besides, many kinds of sounds are heard here. Yet they are nothing but noises, not a warning of danger. For example, we hear the sounds made by thunder, wind among the reeds, lutes, drums, tambourines, conch-shells, bells, wagons, banging doors, machines, and other things. They are nothing to be afraid of. As the verse says:

If a king be brave, however

Fierce the foe and grim,

Sorrows of humiliation

Do not wait for him.

And again:

Bravest bosoms do not falter,

Fearing heaven's threat:

Summer dries the pools; the Indus

Rises, greater yet.

And once again:

Mothers bear on rare occasions

To the world a chief,

Glad in luck and brave in battle,

Undepressed in grief.

And yet again:

Do not act as does the grass-blade.

Lacking honest pride,

Drooping low in feeble meanness,

Lightly brushed aside.

My master must take this point of view and reinforce his resolution, not fear a mere sound. As the saying goes:

I thought at first that it was full

Of fat; I crept within

And there I did not find a thing

Except some wood and skin.”

“How was that?” asked Rusty. And Victor told the story of

The Jackal and the War-Drum

In a certain region was a jackal whose throat was pinched by hunger. While wandering in search of food, he came upon a king’s battle ground in the midst of a forest. And as he lingered a moment there, he heard a great sound.

This sound troubled his heart exceedingly, so that he fell into deep dejection and said: “Ah me! Disaster is upon me. I am as good as dead already. Who made that sound? What kind of a creature?”

But on peering about, he spied a war-drum that loomed like a mountain-peak, and he thought: “Was that sound its natural voice, or was it induced from without?” Now when the drum was struck by the tips of grasses swaying in the wind, it made the sound, but was dumb at other times.

So he recognized its helplessness, and crept quite near. Indeed, his curiosity led him to strike it himself on both heads, and he became gleeful at the thought: “Aha! After long waiting food comes even to me. For this is sure to be stuffed with meat and fat.”

Having come to this conclusion, he picked a spot, gnawed a hole, and crept in. And though the leather covering was tough, still he had the luck not to break his teeth. But he was disappointed to find it pure wood and skin, and recited a stanza:

Its voice was fierce; I thought it stuffed

With fat, so crept within;

And there I did not find a thing

Except some wood and skin.

So he backed out, laughing to himself, and said:

I thought at first that it was full Of fat, ....

and the rest of it.

“And that is why I say that one should not be troubled by a mere sound.” “But,” said Rusty, “these retainers of mine are terrified and wish to run away. So how am I to reinforce my resolution?” And Victor answered: “Master, they are not to blame. For servants take after the master. You know the proverb:

In case of horse or book or sword, Of woman, man or lute or word, The use or uselessness depends On qualities the user lends.

“Then summon your manhood and remain on this spot until I return, having ascertained the nature of the creature. Then act as seems proper.” “What!” said Rusty, “are you plucky enough to go there?” And Victor answered: “When the master commands, is there any difference between ‘possible’ and ‘impossible’ to the good servant? As the proverb says:

Good servants, when their lords command, Behold no fear on any hand, Cross pathless seas if he desire Or gladly enter flaming fire. The servant who, his lord commanding, Should strive to reach an understanding On labors hard or easy, he King's counselor should never be.”

“If you feel so, my dear fellow,” said Rusty, “then go. Blest be your journeyings.”

So Victor bowed low and set out in the direction of the sound made by Lively. And when he was gone, terror troubled Rusty’s heart, so that he thought: “Ah, I made a sad mistake in trusting him to the point of revealing what is in my mind. Perhaps this Victor will betray me by taking wages from both parties, or from spite at losing his job. For the proverb says:

A servant suffering from a king Dishonor after honoring, Though born and trained to service, will Be eager to destroy him still.

“So I will go elsewhere and wait, in order to learn his purpose. Perhaps Victor might even bring the thing along and try to kill me. As the saying goes:

The trustful strong are caught

By weaker foes with ease;

The wary weak are safe

From strongest enemies.”

Thus he set his mind in order, went elsewhere, and waited all alone, spying on Victor’s procedure.

Meanwhile Victor drew near to Lively, discovered that he was a bull, and reflected gleefully: “Well, well! This is lucky. I shall get Rusty into my power by dangling before him war or peace with this fellow. As the proverb puts it:

All counselors draw profit from

A king in worries pent,

And that is why they always wish

For him, embarrassment.

As men in health require no drug

Their vigor to restore,

So kings, relieved of worry, seek

Their counselors no more.”

With these thoughts in mind, he returned to meet Rusty. And Rusty, seeing him coming, assumed his former attitude in an effort to put a good face on the matter. So when Victor had come near, had bowed low, and had seated himself, Rusty said: “My good fellow, did you see the creature?” “I saw him,” said Victor, “through my master’s grace.” “Are you telling the truth?” asked Rusty. And Victor answered: “How could I report anything else to my gracious master? For the proverb says:

Whoever makes before a king

Small statements, but untrue,

Brings certain ruin on his gods

And on his teacher, too.

And again:

The king incarnates all the gods,

So sing the sages old;

Then treat him like the gods: to him

Let nothing false be told.

And once again:

The king incarnates all the gods,

Yet with a difference:

He pays for good or ill at once;

The gods, a lifetime hence.”

“Yes,” said Rusty, “I suppose you really did see him. The great do not become angry with the mean. As the proverb says:

The hurricane innocuous passes O'er feeble, lowly bending grasses, But tears at lofty trees: the great Their prowess greatly demonstrate.”

And Victor replied: “I knew beforehand that my master would speak thus. So why waste words? I will bring the creature into my gracious master’s presence.” And when Rusty heard this, joy overspread his lotus-face, and his mind felt supreme satisfaction.

Meanwhile Victor returned and called reproachfully to Lively: “Come here, you villainous bull! Come here! Our master Rusty asks why you are not afraid to keep up this meaningless bellowing.” And Lively answered: “My good fellow, who is this person named Rusty?”

“What!” said Victor, “you do not even know our master Rusty?” And he continued with indignation: “The consequences will teach you. He has a retinue of all kinds of animals. He dwells beside the spreading banyan tree. His heart is high with pride. He is lord of life and wealth. His name is Rusty. He is a mighty lion.”

When Lively heard this, he thought himself as good as dead, and he fell into deep dejection, saying: “My dear fellow, you appear to be sympathetic and eloquent. So if you cannot avoid conducting me there, pray cause the master to grant me a gracious safe-conduct.” “You are quite right,” said Victor. “Your request shows savoir faire. For

The earth has a limit,

The mountains, the sea;

The deep thoughts of kings are

Without boundary.

Do you then remain in this spot. Later, when I have held him to an agreement, I will conduct you to him.”

Then Victor returned to Rusty and said: “Master, he is no ordinary creature. He has served as the vehicle of blessed Shiva. And when I questioned him, he said: ‘Great Shiva was satisfied with me and bade me crop the grass beside the Jumna. Why make a long story of it? The blessed one has given me this forest as a playground.’”

At this Rusty was frightened, and he said: “I knew it, I knew it. Only by special favor of the gods do creatures wander in a wild wood, bellowing like that, and fearlessly cropping the grass. But what did you say?”

“Master,” said Victor, “I said: ‘This forest is the domain of Rusty, vehicle of Shiva’s passionate wife. Hence you come as a guest. You must meet him, must spend your time in brotherly love, must eat, drink, work, play, and make your home with him.’ All this he promised, adding: ‘You must make your master grant me a safe-conduct.’ As to that, the master is the sole judge.”

At this Rusty was delighted and said: “Splendid, my intelligent servant, splendid! You must have taken counsel with my own heart before speaking. I grant him a safe-conduct. You must hasten to conduct him here, but not until he too has bound himself by oath toward me. Yes, there is sound sense in the saying:

Polished, fully tested,

Sturdy too, and straight

Are the pillars proper

To a house—or state.

Again:

Wit is shown in hours of crisis:

Doctors' wit, in sore disease;

Counselors', in patching friendship—

All are wise in hours of ease.”

Now Victor thought, as he set out to meet Lively: “Well, well! The master is gracious to me and ready to do my bidding. So there is none more blest than I. For

Four things are nectar: milky food;

A fire in chilly weather;

An honor granted by the king;

And loved ones, come together.”

So he found Lively, and said respectfully: “My friend, I won the old master’s favor for you, and made him give you a safe-conduct. You may go without anxiety. Still, though you have favor in the eyes of the king, you must act in agreement with me. You must not play the haughty master. I for my part, in alliance with you, will take the rôle of counselor, and bear the whole burden of administration. Thus we shall both enjoy royal affluence. For

A sinful chase—yet men can stalk

The treasures of the crown:

One starts the quarry from its lair;

Another strikes it down.

And again:

Whoever is too haughty to Pay king's retainers honor due, Will find his feet are tottering— So merchant Strong-Tooth with the king.”

“How was that?” asked Lively. And Victor told the story of

There is a city called Growing City on the earth’s surface. In it lived a merchant named Strong-Tooth who directed the whole administration. So long as he handled city business and royal business, all the inhabitants were satisfied. Why spin it out? Nobody ever saw or heard of his like for cleverness. For there is much wisdom in the proverb:

Suppose he minds the king's affairs,

The common people hate him;

And if he plays the democrat,

The prince will execrate him:

So, since the struggling interests

Are wholly contradictory,

A manager is hard to find

Who gives them both the victory.

While he occupied this position, he once had a daughter married. To the wedding he invited all the townspeople and the king’s entourage, paid them much honor, feasted them, and regaled them with gifts of garments and the like. And when the wedding was over, he conducted the king home with his ladies and showed him reverence.

Now the king had a house-cleaning drudge named Bull, who took a seat that did not belong to him—this in the very palace, and in the presence of the king’s professor. So Strong-Tooth administered a cuffing and drove him out. From that moment the humiliation so rankled in Bull’s inner soul that he had no rest even at night. Yet he thought: “After all, why should I grow thin? It does me no good. For I cannot possibly hurt him. And there is sense in the saying:

Indulge no angry, shameless wish

To hurt, unless you can:

The chick-pea, hopping up and down,

Will crack no frying-pan.”

Now one morning, as he was sweeping near the bed where the king lay half awake, he said: “What impudence! Strong-Tooth kisses the queen.” When the king heard this, he jumped up in a hurry, crying: “Come, come, Bull! Is that thing true that you were muttering? Has the queen been kissed by Strong-Tooth?”

“O King,” answered Bull, “I was awake all night because I am passionately fond of gambling. So sleep overpowered me even when I was busy with my sweeping. I do not know what I said.”

But the jealous king thought: “Yes, he has free entrance to my palace. So has Strong-Tooth. Perhaps he actually saw the fellow hugging the queen. For the proverb says:

Whate'er a man desires, sees, does

In broad daylight,

Still mindful, he will say or do

Asleep at night.

And again:

Whatever secrets, good or ill, Men in their bosoms keep, Are soon betrayed when they are drunk Or talking in their sleep.

In any case, what doubt can there be where a woman is concerned?

With one she tries the gossip's art;

Her glances with a second flirt;

She holds another in her heart:

Whom does she love enough to hurt?

And again:

The logs will glut the hungry fire,

The rivers glut the sea's desire,

And Death with life be glutted, when

The flirt has had enough of men.

No chance, no corner dark,

No man to woo;

Then, holy sage, you find

A woman true.

And once again:

The blunderhead who thinks:

‘My love loves me,’

Is ever in her power;

A tame bird, he.”

After all this lamentation, he withdrew his favor forthwith from Strong-Tooth. Not to make a long story of it, he forbade his entrance at court. When Strong-Tooth saw that the monarch’s favor was suddenly withdrawn, he thought: “Ah me! There is wisdom in the stanza:

Whom does not fortune render proud?

Whom does not death lay low?

To what roué do passions not

Bring never ceasing woe?

What beggar can be dignified?

Whose heart no woman stings?

Who, trapped by scamps, comes safely off?

Who is beloved of kings?

And again:

Who ever saw or heard A gambler's truthful word, A neat and cleanly crow, A woman going slow In love, a kindly snake, A eunuch's pluck awake, A drunkard's love of science, A king in friends' alliance?

And yet I never committed an unfriendly act against the king—or anyone else—not even in a dream, not even by mere words. So why does the king withdraw his favor from me?”

Now one day Bull, the sweeper, saw Strong-Tooth stopped at the palace gate, and he laughed aloud, saying to the doorkeepers: “Be careful, doorkeepers! This fellow Strong-Tooth’s temper has been spoiled by the king’s favor and he dispenses arrests and releases. If you stop him, you

will get a cuffing, just like me.”

And Strong-Tooth reflected on hearing this: “I see. It was Bull’s doing. Well, there is sense in the proverb:

Though foolish, base, and lacking pride, A servant at the monarch's side Will have his honor satisfied. Though fashioned on a cowardly plan And mean, a royal servant can Resent affronts from any man.”

After this lamentation he went home, abashed and deeply stirred. Then he summoned Bull in the evening, gave him two garments as an honorable present, and said: “My good fellow, I did not drive you out by order of the king. It was because I saw you, in the chaplain’s presence, sitting where you did not belong, that I humiliated you.”

Now Bull received the two garments as if they were the Kingdom of Heaven, and feeling intense satisfaction, he said: “Friend merchant, I forgive you. You will soon see the reward of the honor shown me in the king’s favor and such things.” With this he departed in high glee. For there is wisdom in the saying:

A little thing will lift him high,

A little make him fall:

'Twixt balance-beam and scamp there is

No difference at all.

On the next day Bull entered the palace, and did his sweeping. And while the king lay half awake, he said: “What intelligence! When our king sits at stool, he eats a cucumber.”

Now the king, hearing this, rose in amazement and said: “Come, come, Bull! What twaddle is this? But I remember that you are a house-servant and do not kill you. Did you ever see me engaged in that occupation?”

“O King,” said Bull, “I was awake all night because I am passionately fond of gambling. So drowsiness overcame me in

the very act of doing my sweeping. I do not know what I was muttering. Pardon me, master. I was really asleep.”

Then the king thought: “Why, from the day of my birth I never ate a cucumber while engaged in that occupation. And since this blockhead has talked unimaginable nonsense about me, it must be the same with Strong-Tooth. This being so, I made a mistake in taking the poor man’s honors from him. Nothing of the sort is conceivable with such men. And in his absence all the king’s business and city business is at loose ends.”

After thus considering the matter from every point of view, he summoned Strong-Tooth, presented him with gems from his own person and with garments, and reinstated him.

“And that is why I say:

Whoever is too haughty to Pay king's retainers honor due, ....

and the rest of it.” “My dear fellow,” said Lively, “your argument is quite convincing. Let it be as you say.”

After this Victor took him to Rusty and said: “O King, here is Lively. I have brought him hither. The future rests with the king.” Then Lively bowed respectfully and stood before the king in a modest attitude. Thereupon Rusty extended over him a right paw plump, firm, massive, adorned with claws as formidable as thunderbolts, and said with deference: “Do you enjoy health? Why do you dwell in this wild wood?”

Thus questioned, Lively related accurately his separation from merchant Increase and the others. And Rusty, after listening to the story, said: “Have no fear, comrade. Protected by my paws, lead your own life in this forest. Furthermore, you must always take your amusements in my vicinity. For this forest has many drawbacks, since it swarms with numerous savage creatures.” And Lively made answer: “Very well, O King.”

Then the king of beasts went down to the bank of the Jumna, drank and bathed his fill, and plunged again into the forest, wherever inclination led him.

Thus the time passed, the mutual affection of the two increasing daily. Now Lively had assimilated solid intelligence by mastering numerous authoritative works, so that in a very few days he planted discernment in Rusty, dull as was his mind. He weaned him from forest habits and taught him village manners. Why spin it out? Lively and Rusty did nothing but hold secret confabulations every day.

This being so, all the other animals of the retinue were kept at a distance. As for the two jackals, they did not even

have the entrée. More than that, as soon as they lacked the lion’s prowess, the whole company of animals, not excluding the two jackals, suffered grievously from hunger and huddled together. As the proverb puts it:

A king, though proud and pure of birth,

Will see his servants flee

A court where no rewards are won,

As birds a withered tree.

And again:

They may be honored gentlemen,

They may devoted be,

Yet servants leave a monarch who

Forgets the salary.

While, on the other hand:

A king may scold Yet servants hold, If he but pay Upon the day.

Indeed, all the creatures in this world, adopting cajolery or one of the other three devices, live by eating one another. For example:

Some eat the countries; these are kings; The doctors, those whom sickness stings; The merchants, those who buy their things; And learned men, the fools. The married are the clergy's meat; The thieves devour the indiscreet; The flirts their eager lovers eat; And Labor eats us all. They keep deceitful snares in play; They lie in wait by night and day; And when occasion offers, prey Like fish on lesser fish.

Now Cheek and Victor, robbed of their master’s favor, took counsel together—for their throats were pinched with hunger. And Victor said: “Cheek, my noble friend, we two seem to have lost our job. For Rusty takes such delight in Lively’s conversation that he neglects his business. And the whole court is scattered every which way. What is to be done?”

And Cheek replied: “Even if the master does not take your advice, still you should admonish him to correct his faults. For the proverb says:

Good counselors should warn a king

Although he pay no heed

(As Vidur warned the monarch blind)

To cease from evil deed.

And again:

Good counselors or drivers may not duck From kings or elephants that run amuck.

Besides, in introducing this grass-nibbler to the master you were handling live coals.” And Victor answered: “You are right. The fault is mine, not the master’s. As the saying goes:

The jackal at the ram-fight;

And we, when tricked by June;

The meddling friend—were playing

A self-defeating tune.”

“How was that?” asked Cheek. And Victor told three stories in one, called

In a certain district there was a monastery in a secluded spot. In it lived a holy man named Godly, who in course of time acquired a great sum of money by selling finely woven garments, the numerous offerings of the faithful for whom he performed sacrifices.

As a result, he trusted no man, and kept his treasure under his arm by night and day. For there is wisdom in the proverb:

Money causes pain in getting; In the keeping, pain and fretting; Pain in loss and pain in spending: Damn the trouble never ending!

Now a rogue named June, who took other people’s money from them, observed the treasure under his arm, and reflected: “How am I to take this treasure from him? In the first place, I cannot pierce the wall of the cell, which is compactly built of solid stone. And I cannot enter the door, which is too high. I will talk to him, win his confidence, and become his disciple, for he will be in my power when I have his confidence. As the proverb says:

None lacking shrewdness flatter well; None but a lover plays the swell; No saints are found in judgment seats; No clear, straightforward speaker cheats.”

Having thus made up his mind, he drew near to Godly, uttered the words: “Glory to Shiva. Amen,” fell flat on his face, and spoke with deference: “O holy sir! All life is vanity. Youth slips by like a mountain torrent. The days of our life are like a fire in chaff. Delights of the flesh are as the shadow of a cloud. Union with son, friend, servant, wife, is but a dream. All this I discern clearly. What shall I do that I may safely cross the sea of many lives?”

On hearing this, Godly said respectfully: “My son, blest

are you, being thus indifferent to the world in early youth. What says the proverb?

'Tis only saints in youth That can be saints in truth: Ah, who is not a saint When ebbing passions faint?

And again:

First mind, then body ages In case of holy sages: The body ages first, Mind never, in the worst.

“And as for your search to find a means of safely crossing the sea of many lives, just listen to this:

A hangman with his matted hair, Or serf, or other man, through prayer To holy Shiva, changes caste, Becomes pure Brahman at the last. Six syllables, a little prayer; A single blossom resting there On Shiva's symbol—and on earth No further pain, no later birth.”

When he had listened to this, June clasped the holy man’s feet and said deferentially: “This being so, holy sir, pray do me the favor of imposing a vow.”

“My son,” answered Godly, “I am ready to oblige you. But you must not enter my cell by night. For renunciation is recommended to ascetics, to you and to me as well. As the proverb puts it:

Ascetics come to grief through greed; And kings, who evil counsels heed; Children through petting, wives through wine, Through wicked sons a noble line; A Brahman through unstudied books, A character through haunting crooks; A farm is ruined through neglect; And friendship, lacking kind respect; Love dies through absence; fortunes crash Through naughtiness; and hoarded cash Through carelessness or giving rash.

So, after taking the vow, you must sleep in a hut of thatch at the monastery gate.”

“Holy sir,” said the other, “your prescription is the law of my life. I shall need it in the next world.” So, the

sleeping arrangements being made, Godly graciously gave him initiation and granted discipleship. June for his part made the holy man very happy by rubbing his hands and feet, bringing writing-paper, and other services. Still, Godly kept his treasure under his arm.

As the time passed in this manner, June reflected: “Dear me! Do what I will, he does not trust me. So shall I kill him with a knife in broad daylight? Or give him poison? Or butcher him like a beast?”

While he was reflecting thus, the son of a pupil of Godly’s came from the village, bearing an invitation. And he said: “Holy sir, pray come to my house for the ceremony of the sacred thread.” And when Godly heard this, he started with June.

Now as he traveled, he came to a river, seeing which he took the treasure from under his arm, wrapped it carefully in his patched ascetic robe, worshiped the appropriate gods, and said to June: “June, I must step aside. Please keep careful watch of this robe and of the necessary until I return.” With these words he moved away. And as soon as he was out of sight, June seized the treasure and decamped.

The Jackal at the Ram-fight

Now Godly sat down perfectly carefree, for his disciple’s countless virtues had lulled his suspicions. As he rested, he saw a herd of rams, and two of them fighting. These two would angrily draw apart and dash together, their slablike foreheads crashing so that blood flowed freely. This spectacle attracted a jackal whose soul was in the fetters of carnivorous desire, and he stood between the two, lapping up the blood.

When Godly observed this, he thought: “Well, well! This is

a dull-witted jackal. If he happens to be between just when they crash, he will certainly meet death. This inference seems inescapable to me.”

Now the next time, being greedy as ever to lap up the blood, the jackal did not move away, was caught between the crashing heads, and was killed. Then Godly said: “The jackal at the ram-fight,” and grieving for him, started to resume his treasure.

He returned in no haste, but when he failed to find June, he hurried through a ceremony of purification, then examined his robe. Finding the treasure gone, he fell to the ground in a swoon, murmuring: “Oh, oh! I am robbed.” In a moment he came to himself, rose again, and started to scream: “June, June! Where did you go after cheating me? Give me answer!” With this repeated lamentation he moved slowly on, picking up his disciple’s tracks and muttering: “And we, when tricked by June.”

The Weaver’s Wife

Now as he walked along, Godly spied a weaver who with his wife was on his way to a neighboring city for liquor to drink, and he called out: “Look here, my good fellow! I come to you a guest, brought by the evening sun. I do not know a soul in the village. Let me receive the treatment due a guest. For the proverb says:

No stranger may be turned aside Who seeks your door at eventide; Nay, honor him and you shall be Transmuted into deity.

And again:

Some straw, a floor, and water,

With kindly words beside:

These four are never wanting

Where pious folk abide.

And once again:

The sacred fires by kindly word And Indra by the chair is stirred, Krishna by water for the feet, The Lord of All by things to eat.”

On hearing this, the weaver said to his wife: “Go, my dear. Take this guest to the house. Treat him hospitably, giving him water for the feet, food, a bed, and so on. And stay in the house yourself. I will bring plenty of wine and meat for you.” With this he went farther.

So the wife started home with Godly, and she showed a laughing countenance, for she was a whore and had a certain swain in mind. Indeed, there is sense in the verse:

When night is dark

And dark the day,

When streets are mired

With sticky clay,

When husband lingers

Far away,

The flirt becomes

Supremely gay.

The wench cares not

A straw to miss

The covered couch,

The husband's kiss,

The pleasant bed;

In place of this

She ever seeks

A stolen bliss.

And again:

For stranger men

The slut will see

The ruin of

Her family,

The world's reproach,

The jailer's key—

Will risk a death

She cannot flee.

Then she went home, offered Godly a rickety cot and said: “My holy sir, a woman friend has come from the village and I must speak to her. I will be back directly. Meanwhile, you may stay in our house. But please be careful.” With this she put on her best things and started to find her swain.

At this moment she ran into her husband, clasping a jug of wine. He was reeling drunk, his hair was towsled, and he stumbled at every step. She ran when she saw him, entered the house, took off her finery, and appeared as usual.

Now the weaver had seen her flee, had observed the finery,

and since he had previously heard the gossip that went the rounds about her, his heart was troubled and anger overcame him. So he entered the house and said: “You wench! You whore! Where were you going?”

And she replied: “I have not been out since I left you. What is this drunken twaddle? There is sense in the proverb:

After wine and fever, these

Selfsame symptoms come:

Shaking, falling to the ground,

Mad delirium.

And again:

The setting sun and drunken man

Are both a fiery red;

They sink in naked helplessness;

Their dignity is dead.”

When he had taken the scolding and had noticed her change of dress, he said: “Whore! I have heard gossip about you for a long time. Today I have seen the proof. I am going to give you what you deserve.” So he beat her limp with a club, tied her firmly to a post, and fell into a drunken slumber.

At this juncture her friend, the barber’s wife, learning that the weaver was asleep, came in and said: “My dear, he is waiting for you over there—you know who. Go at once.” But the weaver’s wife replied: “Just see what a fix I am in. How can I go? You must return and tell my adorer that I cannot possibly meet him there at this moment.”

“My dear,” said the barber’s wife, “do not say things like that. For a wench of spirit this is no way to behave. As the saying goes:

Those who earn the name of blessed

Show a camel-like persistence

When they pluck the fruit of pleasure,

Counting neither toil nor distance.

And again:

As the other world is doubtful

And as scandal misses truth,

When you've hooked another's lover,

Best enjoy the fruit of youth.

And once again:

Fate may rob him of his manhood, He may handsome be or ugly, Yet a wench, whate'er it cost her, Entertains her lover snugly.”

“Very fine indeed,” said the weaver’s wife. “But tell me how I am to go when I am tied fast. And here lies my husband—the brute!” “My dear,” said the barber’s wife, “he is helpless with drink and will not wake until the sun’s rays reach him. I will set you free and take your place myself. But you must hurry back when you have entertained your admirer.”

This she did, and a moment later the weaver rose a little mollified, and said drunkenly: “Come, you nagger! If you will stay at home after today and stop nagging, I will set you free.” The barber’s wife said nothing, fearing that her voice would betray her. Even when he repeated his offer, she made no answer. Then he became angry and cut off her nose with a sharp knife. And he said: “Whore! Now you can stay there. I shall not be nice to you again.” So he fell asleep, muttering. Now Godly, having lost his money, was so tormented by hunger that he could not sleep, and was a witness of all that the women did.

Presently the weaver’s wife, after enjoying the full delight of love with her swain, came home and said to the barber’s wife: “Well, are you all right? I hope that brute did not get up while I was gone.” And the barber’s wife answered: “The rest of me is all right. But I’ve lost my nose. Set me free quick, before he wakes up. I want to go home. If not, he will do something worse next time, cut off ears and things.”

So the wench freed the barber’s wife, took her former position, and cried reproachfully: “Oh, you dreadful simpleton! I am a true wife, a model of faithfulness. What man is able to violate or disfigure me? Listen, ye guardian deities of the world!

Earth, heaven, and death, the feeling mind, Sun, moon, and water, fire and wind, Both twilights, justice, day and night Discern man's conduct, wrong or right.

So, if I am a faithful wife, may these gods make my nose grow again as it was before. More than that, if I have had so much as a secret desire for a strange man, may they reduce me to ashes.”

After this explosion, she said to him directly: “Look, you villain! By virtue of my faithfulness my nose has grown as it was before.” And when he took a torch and examined her, he found her nose as it was originally, and a great pool of blood on the floor. At this he was amazed, released her from the cords, and flattered her with a hundred wheedling endearments.

Now Godly had seen the whole business. And he was amazed and said:

“Learn science with the gods above

Or imps in nether space,

Yet women's wit will rival it:

How keep them in their place?

Behold the faults with woman born:

Impurity, and heartless scorn,

Untruth, and folly, reckless heat,

Excessive greediness, deceit.

Be not enslaved by women's charm,

Nor wish them growth in power to harm:

Their slaves, of manly feeling stripped,

Are tame, pet crows whose wings are clipped.

Honey in a woman's words,

Poison in her breast:

So, although you taste her lip,

Drub her on the chest.

This palace filled with vice, this field where sprouts

Suspicion's crop, this whirling pool of doubts,

This town of recklessness, sin's aggregate,

This house where frauds by hundreds lie in wait,

This basketful of riddling sham and quip

O'er guessing which our best and bravest trip,

This woman, this machine, this nectar-bane—

Who set it here, to make religion vain?

A bosom hard is praised, a forehead low,

A fickle glance, a mumbling speech and slow,

Thick hips, a heart that constant tremors move,

A natural twist in hair, and twists in love.

Their virtues are a pack of vices. Then

Let beasts adore the fawn-eyed things, not men.

For reasons good they laugh or weep;

They trust you not, your trust they keep:

These graveyard urns, oh, haunt them not!

Keep kin and conduct free from spot.

The lion o'er whose awful face

Falls fierce the towsled mane,

The elephant upon whose cheeks

Streams ichor's glistening rain,

The men of wit or courage who

In books or battles gleam,

In presence of their females, all

Turn into cowards supreme.

And once more:

This gunja-fruit (oh, what was God about?) Is poisonous within, and sweet without.”

In these meditations the night dragged drearily for the

holy man. Meanwhile the go-between went home with her nose cut off, and reflected: “What is to be done now? How is this great deficiency to be concealed?”

The night during which she pondered thus, her husband spent in the king’s palace, practicing his trade. At dawn he came home and, being eager to begin his thriving business with the townspeople, he stopped at the door and called to her: “My dear, bring me my razor-case at once. The townspeople need my services.”

Hereupon an idea occurred to the noseless woman. She remained in the house, but sent him a single razor. And the barber, angry because the entire case had not been delivered, flung the razor in her direction. This gave the wench her opportunity. Lifting her hands to heaven, she dashed from the house, screaming with all her might: “Oh, oh, oh! The ruffian! I was always a faithful wife. Look! He cut off my nose. Save me, save me!”

Hereupon the police arrived, thrashed the barber limp, tied him fast, and took him to court with his wife whose nose was gone. And the judges asked him: “Why did you do this ghastly thing to your wife?” Then, his wits being so addled by astonishment that he could give no answer, the jurymen quoted law:

“The guilty man is terrified By reason of his crime. His pride Is gone, his powers of speaking fail, His glances rove, his face is pale.

And again:

The sweat appears upon his brow, He stumbles on, he knows not how, His face is pale, and all he utters Is much distorted; for he stutters. The culprit always may be found To shake, and gaze upon the ground: Observe the signs as best you can And shrewdly pick the guilty man.

While, on the other hand:

The innocent is self-reliant; His speech is clear, his glance defiant; His countenance is calm and free; His indignation makes his plea.

The prisoner is obviously guilty. The legal penalty for assaulting a woman is death. Let him be impaled.”

But Godly, seeing him led to the place of execution, went to the officers of justice and said: “Gentlemen, you make a mistake in putting this wretched barber to death. His conduct has been correct. Pray listen to these words of mine:

The jackal at the ram-fight; And we, when tricked by June; The meddling friend—were playing A self-defeating tune.”

So the officers said: “How was that, holy sir?” Then Godly related to them the three stories, complete in every detail. And they were all astonished as they listened. They set the barber free, and said:

“Slay not a woman, Brahman, child, An invalid or hermit mild: In case of major dereliction, Disfigurement is the infliction.

Now she has lost her nose through her own act. As additional punishment from the king, let her ears be cut off.” When this had been done, Godly, strengthening his spirit by the two examples, returned to his own monastery.

“And that is why I say:

The jackal at the ram-fight, ....

and the rest of it.”

“Well,” said Cheek, “such being the case, what are you and I to do?” And Victor answered: “Even in these circumstances, I shall have a flash of intelligence, showing me how to separate Lively from the king. Besides, he has fallen into serious vice, has our master Rusty. For

Mad folly stings

The greatest kings,

Who then embrace a vice;

But servants' care

Should check them there

By means of learning nice.”

“Into what vice has our master Rusty fallen?” asked Cheek. And Victor replied: “There are seven vices in the world, namely:

Drink, women, hunting, scolding, dice, Greed, cruelty: these seven are vice.

These, however, really make a single vice, called ‘attachment,’ with seven subdivisions.” Then Cheek inquired: “Is there only a single fundamental vice, or are there others also?”

And Victor expounded: “There are in the world five situations fundamentally vicious.” And when Cheek asked: “How are they differentiated?” Victor continued: “They are called: (1) deficiency, (2) corruption, (3) attachment, (4) devastation, (5) mistaken policy.

“To begin at the beginning, the vice called ‘deficiency’ means the non-existence of one or another of these: king, counselor, people, fortress, treasure, punitive power, friends.

“Secondly, when subjects, whether foreign or native, become restless, whether individually or en masse, there arises the vicious situation called ‘corruption.’

“‘Attachment’ was explained above, in the words:

Drink, women, hunting, ....

and the rest of it. Here there is a love-group (drink, women, hunting, dice) and a wrath-group (scolding, and the rest). A man thwarted in the love-group becomes obnoxious to the wrath-group. The love-group requires no elucidation. The wrath-group, however, threefold as already described, needs some further characterization. ‘Scolding’ is ill-considered imputation of fault on the part of one bent on injuring an antagonist. ‘Cruelty’ means ruthless and unwarranted refinements in putting to death, imprisonment, mutilation. ‘Greed’ is covetousness pushed to a merciless point. These are the seven subdivisions of the vice of attachment.

“Next, there are eight kinds of devastation: by act of God, fire, water, disease, plague, panic, famine, devil-rain (which is a mere name for excessive rain). This disposes of the vice called ‘devastation.’

“Finally, there is mistaken policy. Where a man makes a mistaken use of the six expedients—peace, war, change of base, entrenchment, alliance, duplicity—adopting war instead of peace, or peace instead of war, or making similar mistakes in regard to the other expedients, there we have the vice of mistaken policy.

“Now our master Rusty has fallen into the very first vice, that of deficiency. For he has been so captivated by Lively that he pays not the smallest heed to counselor or any other of the six supports of his throne. He adopts rather completely a vegetarian morality. So what is the use of a lengthy discussion? Rusty must by all means be detached from Lively. No lamp, no light.”

“How will you detach him?” objected Cheek. “You have not the power.” “My dear fellow,” said Victor, “there is a verse to fit the situation, namely:

In cases where brute force would fail,

A shrewd device may still prevail:

The crow-hen used a golden chain,

And so the dreadful snake was slain.”

“How was that?” asked Cheek. And Victor told

In a certain region grew a great banyan tree. In it lived a crow and his wife, occupying the nest which they had built. But a black snake crawled through the hollow trunk and ate their chicks as fast as they were born, even before baptism. Yet for all his sorrow over this violence, the poor crow could not desert the old familiar banyan and seek another tree. For

Three cannot be induced to go— The deer, the cowardly man, the crow: Three go when insult makes them pant— The lion, hero, elephant.

At last the crow-hen fell at her husband’s feet and said: “My dear lord, a great many children of mine have been eaten by that awful snake. And grief for my loved and lost haunts me until I think of moving. Let us make our home in some other tree. For

No friend like health abounding;

And like disease, no foe;

No love like love of children;

Like hunger-pangs, no woe.

And again:

With fields overhanging rivers,

With wife on flirting bent,

Or in a house with serpents,

No man can be content.

We are living in deadly peril.” At this the crow was dreadfully depressed, and he said: “We have lived in this tree a long time, my dear. We cannot desert it. For

Where water may be sipped, and grass

Be cropped, a deer might live content;

Yet insult will not drive him from

The wood where all his life was spent.

Moreover, by some shrewd device I will bring death upon this villainous and mighty foe.”

“But,” said his wife, “this is a terribly venomous snake. How will you hurt him?” And he replied: “My dear, even if I have not the power to hurt him, still I have friends who possess learning, who have mastered the works on ethics. I will go and get from them some shrewd device of such nature that the villain—curse him!—will soon meet his doom.”

After this indignant speech he went at once to another tree, under which lived a dear friend, a jackal. He courteously called the jackal forth, related all his sorrow, then said: “My friend, what do you consider opportune under the circumstances? The killing of our children is sheer death to my wife and me.”

“My friend,” said the jackal, “I have thought the matter through. You need not put yourself out. That villainous black snake is near his doom by reason of his heartless cruelty. For

Of means to injure brutal foes

You do not need to think,

Since of themselves they fall, like trees

Upon the river's brink.

And there is a story:

A heron ate what fish he could, The bad, indifferent, and good; His greed was never satisfied Till, strangled by a crab, he died.”

“How was that?” asked the crow. And the jackal told the story of

The Heron That Liked Crab-Meat

There was once a heron in a certain place on the edge of a pond. Being old, he sought an easy way of catching fish on which to live. He began by lingering at the edge of his pond, pretending to be quite irresolute, not eating even the fish within his reach.

Now among the fish lived a crab. He drew near and said: “Uncle, why do you neglect today your usual meals and

amusements?” And the heron replied: “So long as I kept fat and flourishing by eating fish, I spent my time pleasantly, enjoying the taste of you. But a great disaster will soon befall you. And as I am old, this will cut short the pleasant course of my life. For this reason I feel depressed.”

“Uncle,” said the crab, “of what nature is the disaster?” And the heron continued: “Today I overheard the talk of a number of fishermen as they passed near the pond. ‘This is a big pond,’ they were saying, ‘full of fish. We will try a cast of the net tomorrow or the day after. But today we will go to the lake near the city.’ This being so, you are lost, my food supply is cut off, I too am lost, and in grief at the thought, I am indifferent to food today.”

Now when the water-dwellers heard the trickster’s report, they all feared for their lives and implored the heron, saying: “Uncle! Father! Brother! Friend! Thinker! Since you are informed of the calamity, you also know the remedy. Pray save us from the jaws of this death.”

Then the heron said: “I am a bird, not competent to contend with men. This, however, I can do. I can transfer you from this pond to another, a bottomless one.” By this artful speech they were so led astray that they said: “Uncle! Friend! Unselfish kinsman! Take me first! Me first! Did you never hear this?

Stout hearts delight to pay the price Of merciful self-sacrifice, Count life as nothing, if it end In gentle service to a friend.”

Then the old rascal laughed in his heart, and took counsel with his mind, thus: “My shrewdness has brought these fishes into my power. They ought to be eaten very comfortably.” Having thus thought it through, he promised what the

thronging fish implored, lifted some in his bill, carried them a certain distance to a slab of stone, and ate them there. Day after day he made the trip with supreme delight and satisfaction, and meeting the fish, kept their confidence by ever new inventions.

One day the crab, disturbed by the fear of death, importuned him with the words: “Uncle, pray save me, too, from the jaws of death.” And the heron reflected: “I am quite tired of this unvarying fish diet. I should like to taste him. He is different, and choice.” So he picked up the crab and flew through the air.

But since he avoided all bodies of water and seemed planning to alight on the sun-scorched rock, the crab asked him: “Uncle, where is that pond without any bottom?” And the heron laughed and said: “Do you see that broad, sun-scorched rock? All the water-dwellers have found repose there. Your turn has now come to find repose.”

Then the crab looked down and saw a great rock of sacrifice, made horrible by heaps of fish-skeletons. And he thought: “Ah me!

Friends are foes and foes are friends As they mar or serve your ends; Few discern where profit tends.

Again:

If you will, with serpents play; Dwell with foemen who betray: Shun your false and foolish friends, Fickle, seeking vicious ends.

Why, he has already eaten these fish whose skeletons are scattered in heaps. So what might be an opportune course of action for me? Yet why do I need to consider?

Man is bidden to chastise Even elders who devise Devious courses, arrogant, Of their duty ignorant.

Again:

Fear fearful things, while yet

No fearful thing appears;

When danger must be met,

Strike, and forget your fears.

So, before he drops me there, I will catch his neck with all four claws.”

When he did so, the heron tried to escape, but being a fool, he found no parry to the grip of the crab’s nippers, and had his head cut off.

Then the crab painfully made his way back to the pond, dragging the heron’s neck as if it had been a lotus-stalk. And when he came among the fish, they said: “Brother, why come back?” Thereupon he showed the head as his credentials and said: “He enticed the water-dwellers from every quarter, deceived them with his prevarications, dropped them on a slab of rock not far away, and ate them. But I—further life being predestined—perceived that he destroyed the trustful, and I have brought back his neck. Forget your worries. All the water-dwellers shall live in peace.”

“And that is why I say:

A heron ate what fish he could, ....

and the rest of it.”

“My friend,” said the crow, “tell me how this villainous snake is to meet his doom.” And the jackal answered: “Go to some spot frequented by a great monarch. There seize a golden chain or a necklace from some wealthy man who guards it carelessly. Deposit this in such a place that when it is recovered, the snake may be killed.”

So the crow and his wife straightway flew off at random, and the wife came upon a certain pond. As she looked about, she saw the women of a king’s court playing in the water, and on the bank they had laid golden chains, pearl necklaces, garments, and gems. One chain of gold the crow-hen seized and started for the tree where she lived.

But when the chamberlains and the eunuchs saw the theft, they picked up clubs and ran in pursuit. Meanwhile, the

crow-hen dropped the golden chain in the snake’s hole and waited at a safe distance.

Now when the king’s men climbed the tree, they found a hole and in it a black snake with swelling hood. So they killed him with their clubs, recovered the golden chain, and went their way. Thereafter the crow and his wife lived in peace.

“And that is why I say:

In cases where brute force would fail, ....

and the rest of it. Furthermore:

Some men permit a petty foe Through purblind heedlessness to grow, Till he who played a petty rôle Grows, like disease, beyond control.

Indeed, there is nothing in the world that the intelligent cannot control. As the saying goes:

Intelligence is power. But where Could power and folly make a pair? The rabbit played upon his pride To fool him; and the lion died.”

“How was that?” asked Cheek. And Victor told the story of

Numskull and the Rabbit

In a part of a forest was a lion drunk with pride, and his name was Numskull. He slaughtered the animals without ceasing. If he saw an animal, he could not spare him.

So all the natives of the forest—deer, boars, buffaloes, wild oxen, rabbits, and others—came together, and with woe-begone countenances, bowed heads, and knees clinging to the ground, they undertook to beseech obsequiously the king of beasts: “Have done, O King, with this merciless, meaningless slaughter of all creatures. It is hostile to happiness in the other world. For the Scripture says:

A thousand future lives

Will pass in wretchedness

For sins a fool commits

His present life to bless.

Again:

What wisdom in a deed

That brings dishonor fell,

That causes loss of trust,

That paves the way to hell?

And yet again:

The ungrateful body, frail

And rank with filth within,

Is such that only fools

For its sake sink in sin.

“Consider these facts, and cease, we pray, to slaughter our generations. For if the master will remain at home, we will of our own motion send him each day for his daily food one animal of the forest. In this way neither the royal sustenance nor our families will be cut short. In this way let the king’s duty be performed. For the proverb says:

The king who tastes his kingdom like

Elixir, bit by bit,

Who does not overtax its life,

Will fully relish it.

The king who madly butchers men,

Their lives as little reckoned

As lives of goats, has one square meal,

But never has a second.

A king desiring profit, guards

His world from evil chance;

With gifts and honors waters it

As florists water plants.

Guard subjects like a cow, nor ask

For milk each passing hour:

A vine must first be sprinkled, then

It ripens fruit and flower.

The monarch-lamp from subjects draws

Tax-oil to keep it bright:

Has any ever noticed kings

That shone by inner light?

A seedling is a tender thing,

And yet, if not neglected,

It comes in time to bearing fruit:

So subjects well protected.

Their subjects form the only source

From which accrue to kings

Their gold, grain, gems, and varied drinks,

And many other things.

The kings who serve the common weal,

Luxuriantly sprout;

The common loss is kingly loss,

Without a shade of doubt.”

After listening to this address, Numskull said: “Well,

gentlemen, you are quite convincing. But if an animal does not come to me every day as I sit here, I promise you I will eat you all.” To this they assented with much relief, and fearlessly roamed the wood. Each day at noon one of them appeared as his dinner, each species taking its turn and providing an individual grown old, or religious, or grief-smitten, or fearful of the loss of son or wife.

One day a rabbit’s turn came, it being rabbit-day. And when all the thronging animals had given him directions, he reflected: “How is it possible to kill this lion—curse him! Yet after all,

In what can wisdom not prevail? In what can resolution fail? What cannot flattery subdue? What cannot enterprise put through?

I can kill even a lion.”