|

|

|

- Below, “bhājya” means “the number to be factored” — as the word occurs frequently, I’ll call it $N$.

- I’ve used the simple imperative mood—find this, try that, etc—instead of “one must find…”, or “…are tried”.

|

|

End of chapter 10 |

|

|

|

Start of chapter 11: factoring |

|

|

|

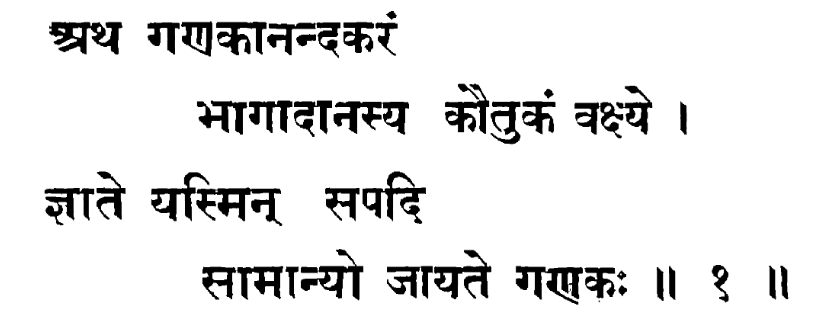

I shall tell you of the delight of mathematicians, the joy of factoring. Learning this turns anyone into a mathematician. |

|

|

|

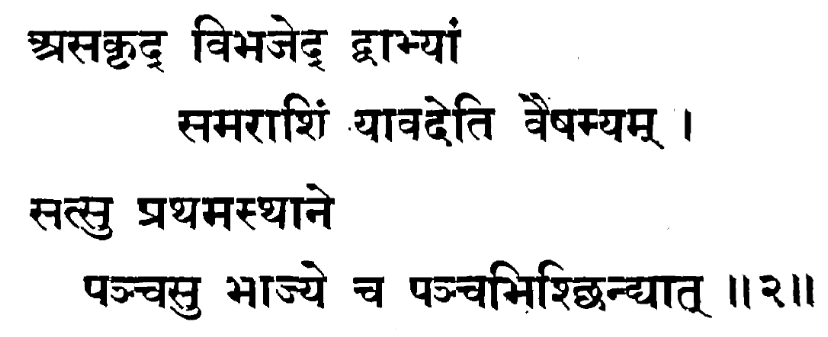

Repeatedly divide an even number by 2, until it becomes odd. If it (the number to be factored) has 5 in the first [units] place, divide by 5. |

|

- asakṛt = repeatedly

- sama = even; viṣama = odd

- In the Sanskrit tradition, numbers were (spoken and) written little-endian, i.e. units place first.

|

|

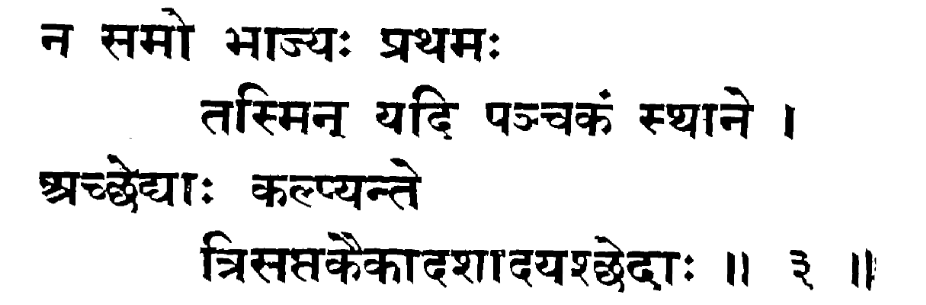

When $N$ is not even nor has $5$ in the units place, try the prime numbers—3, 7, 11, etc—as divisors. |

|

- acchedya = prime number (lit. indivisible)

- tri, saptaka, ekādaśa = 3, 7, 11

|

|

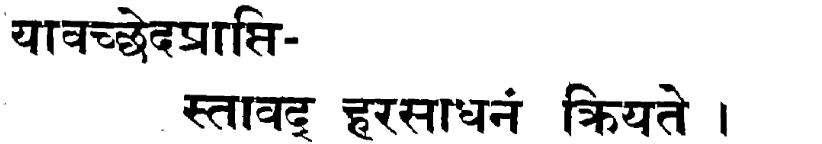

While you find divisors, keep finding divisors. |

|

hara = divisor |

|

If $N$ is a square, then its root is a factor, twice. |

[An alternative method starts here…] |

- varga = square

- mūla = root (literally! Maybe in English the mathematical sense came from elsewhere?)

|

|

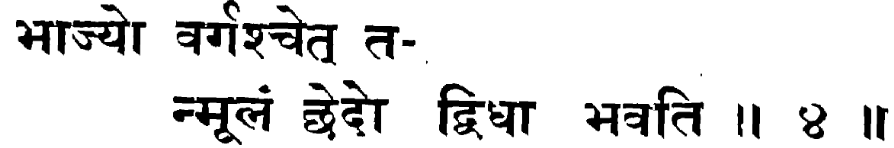

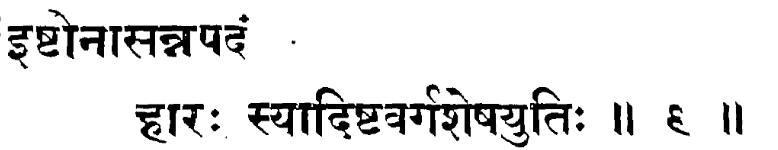

When $N$ is not a square, when added to some square it becomes a square. Then, the sum and difference of the two square-roots are factors. |

That is, there exists some square $s^2$ such that $N + s^2$ is a square, say $N + s^2 = b^2$. Then $b - s$ and $b+ s$ are factors of $N$. |

- pada = square root

- apadaprada = not square (lit. does not give a square root)

- iṣṭa = assumed / unknown

- kṛti = square

- saṃyuti = sum

- viyuti = difference

- hāra = divisor

|

|

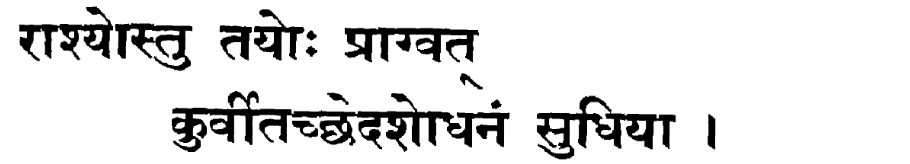

Of these numbers, as before, find factors. |

That is, factorize the $b-s$ and $b+s$ further. |

rāśi = quantity, number — a number that has been written down, e.g. an output of a previous step |

|

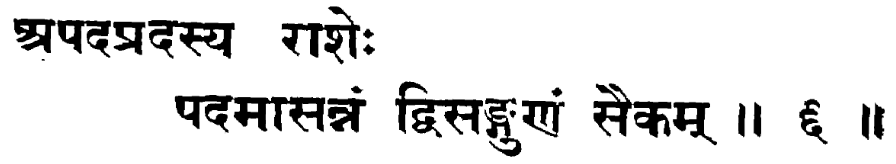

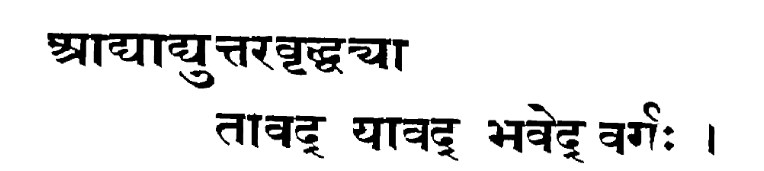

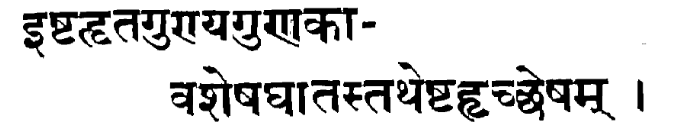

Of a non-square number, find the nearest (integer) square root, double it and add 1… |

|

|

|

…and subtract from it the square-remainder. If the result is a square, then this is the number to be added. |

That is, let $N = m^2 + r$. Then if $2m + 1 - r$ is a square say $s^2$, then $N + s^2$ is $(m^2 + r) + (2m + 1 - r)$ which is $(m + 1)^2$, so we are done, as we have found a square $s^2$ such that $N + s^2$ is a square. |

|

|

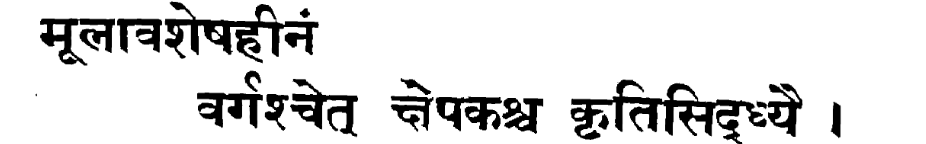

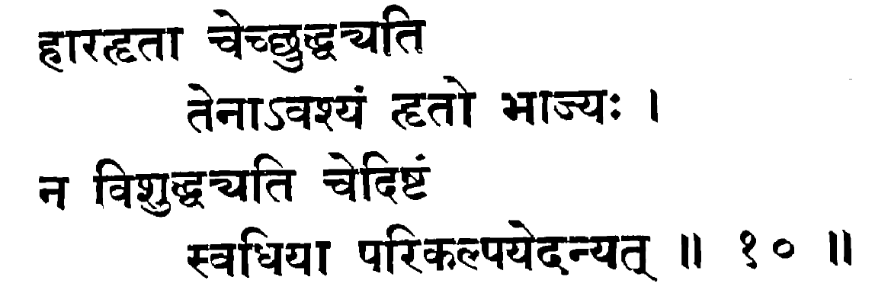

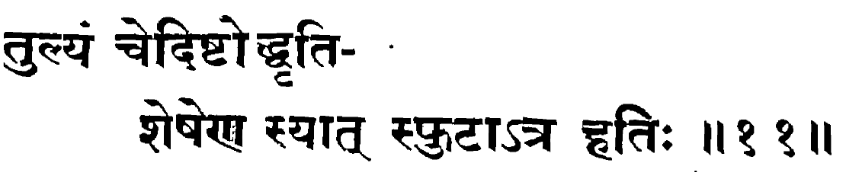

If it is not a square, then further add $2m + 3$… |

The idea is that we’re trying successive values for the smaller square: if $(m + 1)^2 - N$ isn’t a square, then the next option would be to replace $(m + 1)^2$ with $(m + 2)^2$, which is $(m + 1)^2 + (2m + 3)$. |

|

|

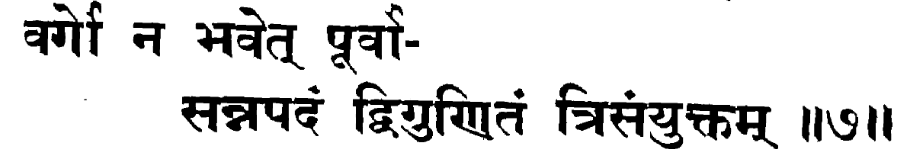

…and so on in arithmetic progression, until you get a square. |

So to $2m + 1 - r$, we’re adding $2m+3$, then $2m+5$ and $2m+7$ and so on. This way, we’re trying to write $N = a^2 - s^2$ by trying, for $a$, successive values $m+1$ then $m+2$ and so on until we find a square $b^2$, but without having to square each time. (We do need to test squareness each time, though.) |

I think uttara = difference and uttaravṛddhi = arithmetic progression. |

|

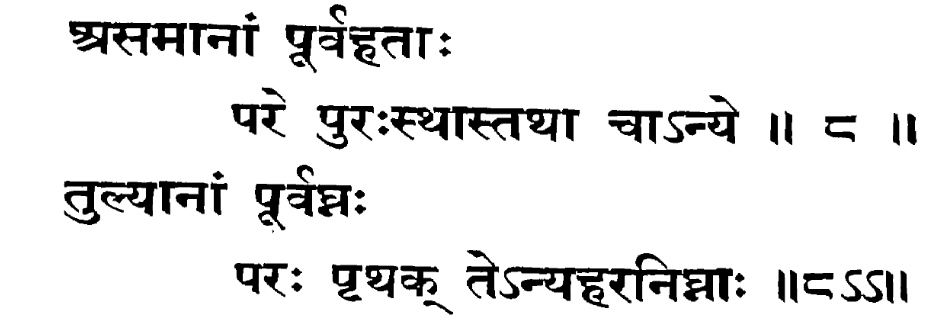

For unequal divisors, put the previous products in front of them, and again separately. For equal divisors, put their products with each of the previous products, and again separately. |

This is a procedure to list all divisors of a number. - For example, say $N = 2 \times 3 \times 5 \times 7 \times 7$.

- Then, write down the list

divisors = [2] - Then append $d \times 3$ for each divisor $d$ in the list currently, and also append $3$ itself. The list becomes:

[2, 2×3, 3]. - Then append $d \times 5$ for each divisor $d$ in the list currently, and also append $5$ itself. The list becomes:

[2, 2×3, 3, 2×5, 2×3×5, 3×5, 5]. - Now for the two $7$s which are equal divisors, append $d \times 7$ and $d \times 7 \times 7$ for each divisor $d$ in the list currently, and also append $7$ and $7 \times 7$ themselves separately.

- This should give all divisors of $N$ (other than $1$, evidently).

|

Took me a while to understand but I think the anvaya is: - pūrvahatāḥ asamānāṃ pare purasthāḥ, tathā ca anye = the prior products, in front of the unique [divisors], and also separately.

- pūrvaghnaḥ tulyānāṃ paraḥ, pṛthak, te anyaharanighnāḥ = the prior products in front of the equal [divisors], and separately, and they [the equal divisors] multiplied by the other (equal?) divisors.

|

|

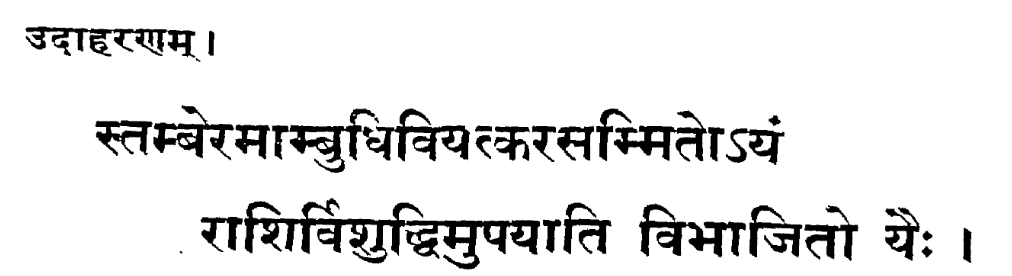

Quickly find the divisors of 2048 and 3125. |

Examples (exercises). Solutions: - Solutions

- For 2048, repeatedly dividing by 2 gives it to be a product of eleven $2$s. We write them down:

[2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2] and their products [2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048]. - For 3125, repeatedly dividing by 5 gives it to be a product of five $5$s. (Etc).

|

- Lit: viśuddhim upayāti vibhājito yaiḥ = those numbers on division by which it leaves zero remainder, i.e. its divisors.

- On the number names:

- stamberama-ambudhi-viyat-kara = 8-4-0-2 = 2048 (stamberama = elephant; sammita = “measured”)

- śara-akṣi-candra-rāma = 5-2-1-3, or 3125. (unmita = "having the measure of")

|

|

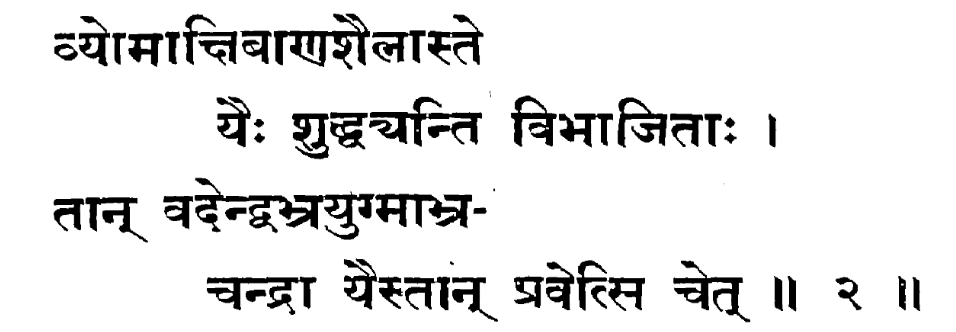

Find the divisors of 7250, and those of 10201. |

Solutions: It turns out that $7520 = 2^5 \times 5 \times 47$, and $10201 = 101^2$. |

- vyoma-akṣi-bāṇa-śaila = 0-2-5-7 = 7520

- indu-abhra-yugma-abhra-candra = 1-0-2-0-1 = 10201

|

|

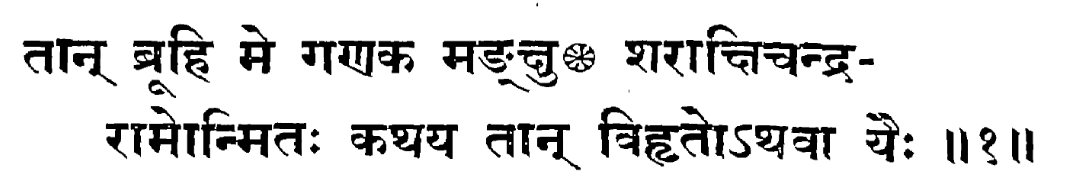

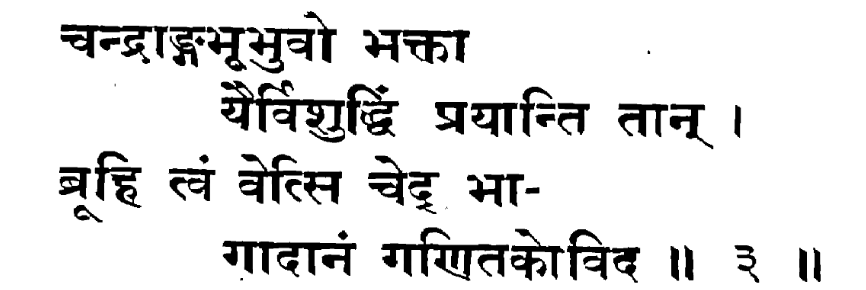

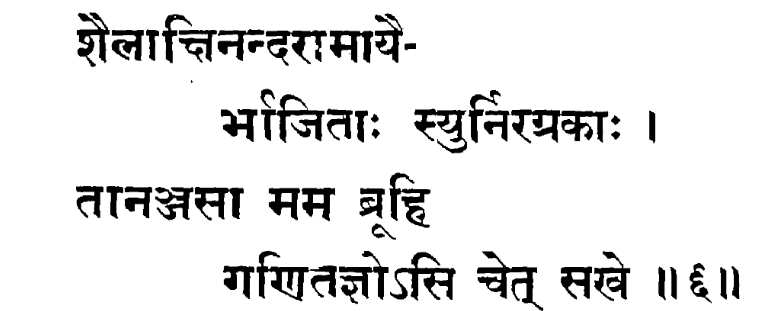

List the divisors of 1161, if you’re a mathematician who knows how to factor. |

Solutions: It turns out that $1161 = 3^3 \times 43$, which we could also get alternatively with $1161 = 34^2 + 5$ and $2\times34 + 1 - 5 = 64$ which is a square, so $1161 = 35^2 - 8^2 = 27 \times 43$. |

candra-aṅga-bhū-bhuvaḥ = 1-6-1-1 = 1161. |

|

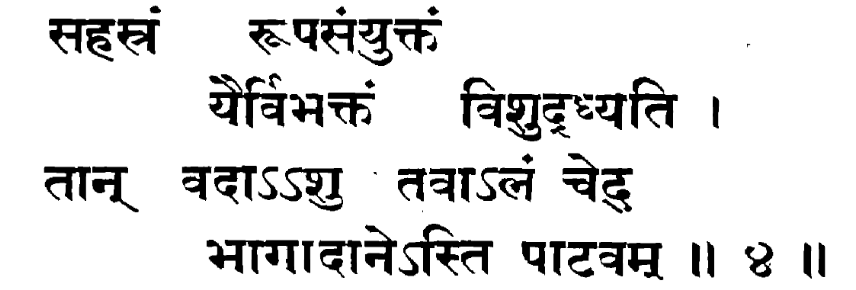

The divisors of 1001 — name them quickly, if you have enough skill in factorization. |

Solutions: The editor and translator use the second method and basically try lots of squares, but we can just use the first method (trial division) for $1001 = 7 \times 11 \times 13$, no? |

sahasraṃ rūpa-saṃyuktaṃ = 1000 + 1 = 1001. |

|

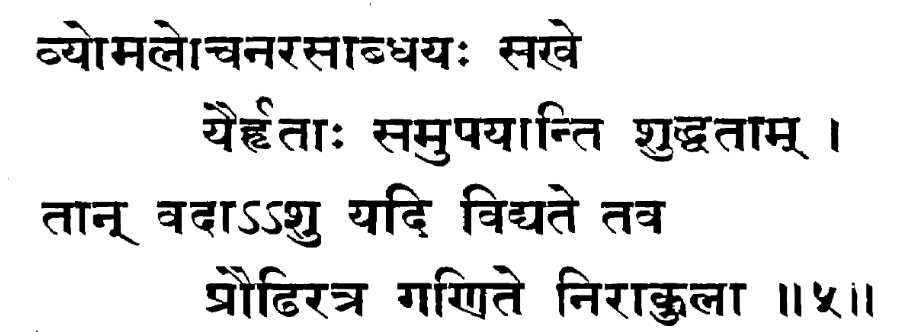

The factors of 4620 — name them quickly, if you have complete proficiency in mathematics. |

Solutions: $4620 = 2^2 \times 3 \times 5 \times 7 \times 11$. So there are 48 factors (or 47 without the 1). Again the editor factorizes 4620 by first removing the factors of 2 and 5 and then factorizing $3 \times 7 \times 11 = 231$ using the difference-of-squares method… but why?! |

vyoma-locana-rasa-abdhayaḥ = 0-2-6-4 = 4620 |

|

Factor 3927. |

Solutions: $3927 = 3 \times 7 \times 11 \times 17$. |

śaila-akṣi-nanda-rāma = 7-2-9-3 = 3927. |

|

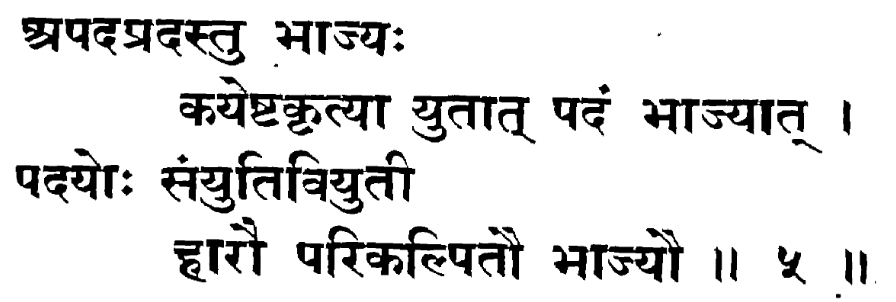

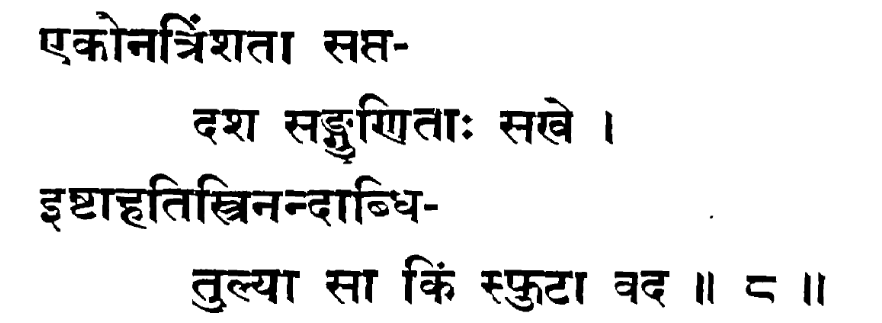

- The nearest square-root, subtracted by some chosen number, is a divisor. If the chosen number when squared and added to the square-remainder…

- …is divisible by this divisor, then surely this divisor is a divisor of the original number.

- If it is not divisible, use your ingenuity to find a different choice.

|

[A third method starts here.] That is, if $N = m^2 + r$, then for some unknown $x$, it is the case that $m - x$ divides $N$. (We want to find $x$.) If we find an $x$ such that $x^2 + r$ is divisible by $m - x$, then we have found $m - x$ as a factor of $N$. (This is actually nontrivial!) In modern terms, the idea is this: write $N = m^2 + r$, and we’re trying to find some $p = m-x$ that divides $N$. Then, $m = p + x \equiv x \pmod p$, and so $N = m^2 + r \equiv x^2 + r \pmod p$. So we want $p = m - x$ to divide $x^2 + r$. That’s the rule. |

That weird glyph that looks like tdṛ = त्दृ is actually is hṛ = हृ :-) |

|

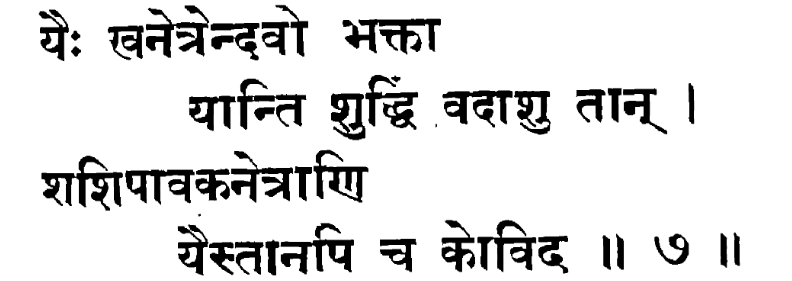

Factors of 120. Factors of 231. |

Solution (if we use this third method): - $120 = 10^2 + 20$, and we want $10 - x$ to divide $x^2 + 20$. We can take $x = 2$, to see that $8$ divides $24$. Similarly, taking $x = 4$ gives $6$ (dividing $36$), and taking $x = 5$ gives $5$ (dividing $45$), and taking $x = 6$ gives $4$ (dividing $56$), and so on. More importantly, note that taking $x = 3$ shows that $7$ does not divide $3^2 + 20 = 29$, so $7$ is not a divisor of $120$.

- For $231 = 15^2 + 6$, we want $15 - x$ to divide $x^2 + 6$. Taking $x=4$ gives $11$ dividing $22$, so $11$ is also a divisor of $231$. Indeed, $231 = 3 \times 7 \times 11$.

|

kha-netra-indu = 0-2-1 = 120. śaśi-pāvaka-netra = 1-3-2 = 231 |

|

By a chosen number, take remainders of both numbers being multiplied. Multiply them, and take remainder modulo the chosen number. If this remainder is the same (as that of the product), then the multiplication is [apparently] correct. |

This is a “sanity check” for verifying a calculation: it’s saying that if you have a calculation $a \times b = c$ and you check that $(a \bmod m) \times (b \bmod m) \equiv (c \bmod m)$, then likely the calculation is correct. |

hati = multiplication |

|

$29 \times 17 = 493$ — check this. |

The editor does the checking mod 3, 5, and 8: mod 3, we can see $2 \times 2 \equiv 4$. Mod 5, we can see $4 \times 2 \equiv 3$. Mod 8, we can see $5 \times 1 \equiv 5$. The calcuation is likely correct. (In modern terms, we could conclude that the multiplication is correct mod $120$, by the Chinese Remainder Theorem.) |

|

|

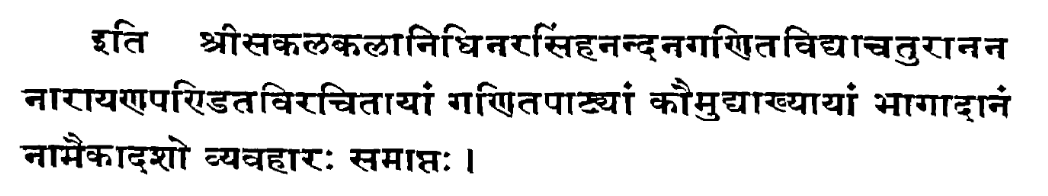

Here ends vyavahāra (chapter) 11, named bhāgādāna (factorization), in the gaṇita text named Kaumudī, by Nārāyaṇa, who is “sakala-kalā-nidhi narasiṃha-nandana” (son of Narasiṃha), and “gaṇita-vidyā-caturānana”. |

|

|